Earths: Japan, the U.S., and the Rare Earth Mining Race

Deep-Sea Dreams: Can Japan and the U.S. Really Break China's Rare Earth Grip?

The headlines blare about Japan and the U.S. teaming up to mine rare earths near Minamitorishima, a small Pacific island. The narrative is clear: a united front against China's dominance in critical minerals. But let's pump the brakes for a second and look at the actual numbers.

Prime Minister Takaichi states Japan will start "demonstration tests" in January to retrieve rare earth-rich mud from 6,000 meters deep. Six thousand meters. That's nearly four miles down. We’re not talking about scooping sand off a beach here. The technical challenges—and, crucially, the costs—are immense.

The surveys suggest abundant rare earth mud near the island, roughly 1,950 kilometers southeast of central Tokyo. Abundant compared to what? The press release glosses over the concentration of rare earth oxides (REO) in this mud compared to existing terrestrial mines. What's the grade? Is it economically viable to extract at that depth, factoring in the energy costs, the specialized equipment, and the environmental impact? These are the questions that get conveniently skipped.

Takaichi mentions "securing various ways to procure rare earths" and "concrete ways for Japan and the U.S. to cooperate." That sounds good, but it's vague. What specific technologies are they planning to use? What's the projected output? What’s the breakdown of investment between Japan and the U.S.? And what exactly does "cooperate" mean – a joint venture, technology sharing, or simply buying the stuff from Japan? The devil, as always, is in the details, and the details are suspiciously absent.

The Reality Check: A Drop in the Bucket?

Let's assume, for the sake of argument, that they do manage to extract significant quantities of rare earths. The global rare earth market is dominated by China, which controls a massive percentage of both mining and processing. Even if this Minamitorishima project is a resounding success (a big "if"), will it really make a dent?

Consider this: global rare earth oxide production in 2023 was approximately 350,000 tonnes. Even a generous estimate of Minamitorishima's potential output – say, 5,000 tonnes per year – is a mere 1.4% of the global total. That's not exactly a game-changer. (And this is the part of the analysis that I find genuinely puzzling, because you would expect them to be more ambitious.)

The geopolitical implications are also worth considering. The U.S. and Japan are clearly motivated by a desire to diversify their supply chains and reduce their dependence on China. But China isn't sitting still. They are actively investing in new rare earth projects around the world and developing alternative technologies. Will this deep-sea mining venture trigger a rare earth arms race? And what are the environmental risks of large-scale deep-sea mining? We're talking about potentially disrupting fragile ecosystems that we barely understand. The cost-benefit analysis here needs to be far more transparent.

The survey data suggests that the seabed around Minamitorishima contains an estimated 16 million tons of rare earth oxides. While that sounds like a lot, it's important to remember that only a fraction of that is likely to be economically recoverable. And even if it is recoverable, the environmental costs could outweigh the benefits.

More Hype Than Substance?

This whole initiative feels more like a symbolic gesture than a practical solution. It's a way for Japan and the U.S. to signal their intent to challenge China's dominance, but the actual impact on the rare earth market is likely to be minimal, at least in the short term. The January "demonstration test" will be crucial. We need to see real data on extraction rates, costs, and environmental impact before we can even begin to assess the viability of this project. Until then, it's just another headline. According to reports, Japan and U.S. to join forces to mine rare earths near Pacific island Japan and U.S. to join forces to mine rare earths near Pacific island.

A Very Expensive Photo Op

-

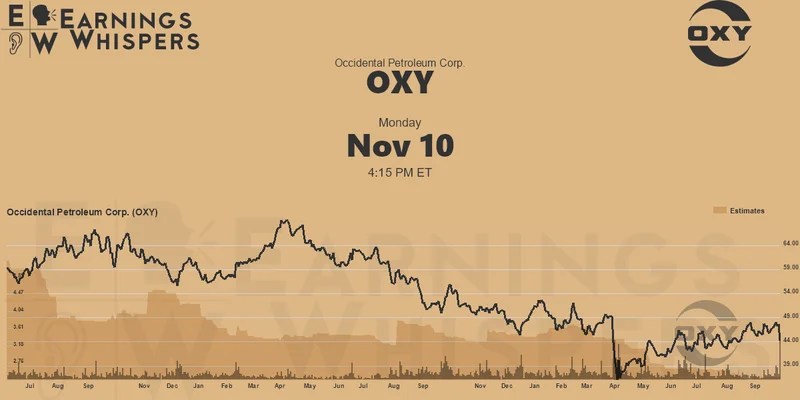

Warren Buffett's OXY Stock Play: The Latest Drama, Buffett's Angle, and Why You Shouldn't Believe the Hype

Solet'sgetthisstraight.Occide...

-

The Business of Plasma Donation: How the Process Works and Who the Key Players Are

Theterm"plasma"suffersfromas...

-

newsmax: What's going on?

[GeneratedTitle]:AreWeReallyS...

-

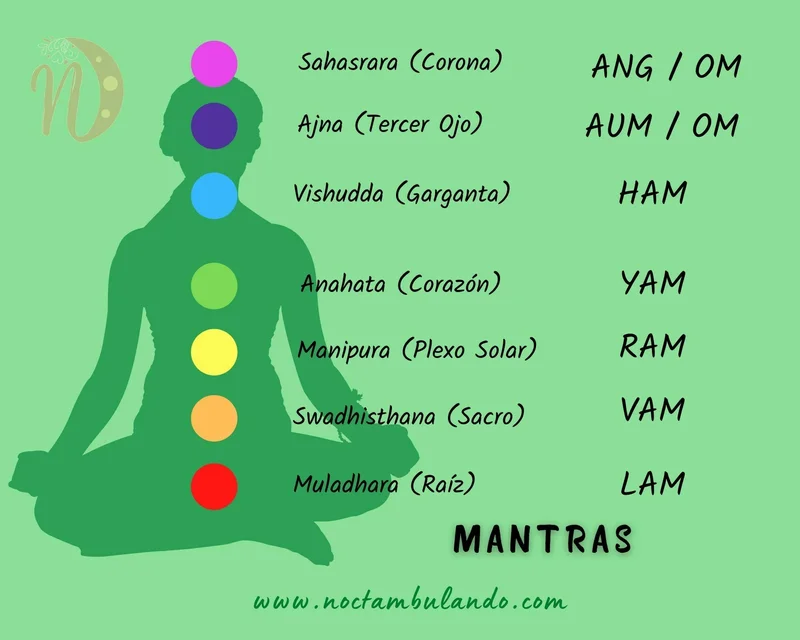

Mantra: A Quantitative Look at the Psychology and Actual Impact

AnAnalysisof'Mantra'asaFunct...

-

Bittensor: The Decentralized AI Vision and Why Wall Street is Suddenly Watching

Ofcourse.Hereisthefeatureart...

- Search

- Recently Published

-

- Dijon: Unpacking the Artist, His Vision, and the SNL Buzz

- Satoshi Nakamoto: Unraveling the Visionary, Defining 'Satoshi,' and Bitcoin's Future

- Cook County Treasurer: Property Tax Bills, Payments, & Why It's Such a Pain

- Allora: The Next Paradigm Shift and What It Means for Humanity

- IRS Relief Payment 2025: Will You Actually See a Direct Deposit?

- The Great Hamburger Collapse: The Real Reason They're Failing and Who's Next

- Nasdaq Composite Rises: What's Driving the Rally and Key Stock Movers

- Zcash's Price Surge: An Analysis of Its Price, Key Endorsements, and Future Outlook

- Pudgy Penguins: DreamWorks Partnership and Crypto Presale

- primerica: What we know so far

- Tag list

-

- carbon trading (2)

- Blockchain (11)

- Decentralization (5)

- Smart Contracts (4)

- Cryptocurrency (26)

- DeFi (5)

- Bitcoin (29)

- Trump (5)

- Ethereum (8)

- Pudgy Penguins (6)

- NFT (5)

- Solana (5)

- cryptocurrency (6)

- XRP (3)

- Airdrop (3)

- MicroStrategy (3)

- Stablecoin (3)

- Digital Assets (3)

- PENGU (3)

- Plasma (5)

- Zcash (6)

- Aster (4)

- investment advisor (4)

- crypto exchange binance (3)

- SX Network (3)